Shirley Sun: "Should We Be Worried About Racialization of Precision Medicine?"

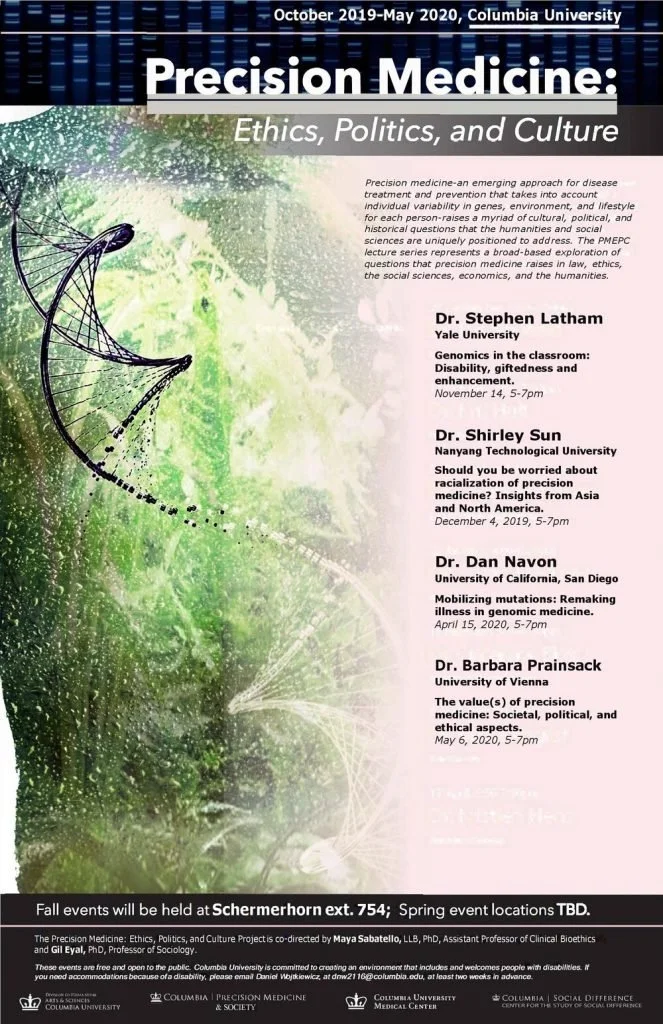

Dr. Shirley Sun, Associate Professor of Sociology with joint courtesy appointments at Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine and the School of Biological Sciences at NTU gave a presentation on December 4, 2019 hosted by the Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics, and Culture working group on the racialization of precision medicine.

In her talk titled “Should you be worried about racialization of precision medicine? Insights from Asia and North America,” Dr. Sun gave an overview of her comparative analysis of provider perspectives on the categorization of genomics data based on race in Singapore, Canada, and the United States.

Her qualitative interviews with healthcare providers reveal the contentions and dilemmas that racialized precision medicine creates for practitioners; on the one hand providers understand that genomic data categorized by race and ethnicity is inherently faulty, and that it is at best a proxy for health behaviors. One provider called this the “poor man’s” genetic testing. On the other hand, data is delivered to these providers in a racialized format and these providers are then tasked to utilize this data to make healthcare decisions for their patients. Data categorized along ethnic and racial lines also provide useful shorthand devices to help patients understand their disease probability.

Dr. Sun warns that racialized findings of precision medicine may be especially challenging for populations that do not have access to resources. Inability to pay for cutting edge therapies or healthcare resources necessary to address disease disparities revealed by precision medicine may contribute to further health inequality among already vulnerable populations that are more likely to be ethnic and racial minority groups. Concerns from providers about patient access to resources were observed in all three sites, despite that healthcare is nationalized in Canada, for example.

The presentation concluded by opening up to questions from the audience. Among other topics, questions regarding the impact of anti-discrimination laws and the importance of provider self-identified demographics (race, ethnicity, gender) emerged. Interestingly, according to Dr. Sun, providers first and foremost identified themselves as healthcare providers before identifying with any race or ethnicity during these interviews. Second, the discussion also opened up to the concern about patients’ access to costly and rare therapies necessary to treat their genetic disorders. Physicians would anecdotally tell stories of patients who had succumbed to such high expenses that they sold their homes and other possessions to pay for treatments. This personal narrative drove home how precision medicine diagnostic abilities were more advanced than treatments, as treatments were rare and prohibitively expensive across both nationalized and privatized healthcare systems.

Approaches to Racial and Ethnic Genomic Variance

Given the importance of race and ethnicity to health in racialized societies like the United States, we see disparate approaches to how genomics are discussed in research. Seeing cancer morbidity and mortality differences among ethnoracial groups as a starting point, Peter O’Donnel and Eileen Dolan (2009) of the University of Chicago suggest “cancer pharmacoethnicity” may be a useful approach. Cancer pharmacoethnicity, according to O’Donnel and Dolan, could hold the potential to be predictive of individual drug responses based on the race or ethnic group these individuals identify with. In contrast, Nancy Krieger and colleagues (2017) of Harvard’s School of Public Health analyzed the racial disparities in estrogen-receptor negative breast cancer among Black and White American women through a socio-political lens. In this report, Krieger’s team demonstrates that it is necessary to look at race as a historically situated category that changes through time. Krieger, Jahn and Waterman illustrate how the high incidence of estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer among Black women compared to White women can be linked to being born under the legalized discrimination of Jim Crow laws. Black women living in states that enforced Jim Crow segregation had a higher odds ratio of estrogen-receptor negative breast cancer, while White women did not show this trend. The highest incidence of this type of breast cancer was evident for Black women born before 1965. This historically situated approach highlights how racialized biologies result from social processes independent of fundamental biological differences.

Krieger, Jahn and Waterman validate a framework that examines racial disparities at the molecular level in a way that foregrounds history and social processes of racialization, and avoids suggesting that observed differences emerge from “fundamental” difference in racial biologies or genotypes.

Socially Situated Genomic Differences

Sociopolitical context is also important from a global perspective. In Cooper et al.’s article (2005) titled “An international comparative study of blood pressure in populations of European vs. African descent,” sociocultural and political impacts on health trends were again highlighted. While in the United States cardiovascular disease is indisputably a more prominent health problem among Blacks, Cooper and colleagues establish that this does not have to do with African Ancestry; in fact, Germanic populations had a higher high blood pressure incidence than any population included in their world-wide study. Through their analysis, the authors bring to the foreground the effects of place and social standing to population-level health in contrast to other research that frame disease as germane to the individuals that make up racial and ethnic populations.

Troy Duster (2003) brings the discussion in focus through his description of the divergent approaches to population-level genomic disease risk. In his comparison of responses to Tay-Sachs and sickle cell anemia genetic screening, Duster emphasizes how genomic disease risk is not simply about the disease, but also about the population it affects and the policy responses enacted. Duster describes how Tay-Sachs is a rapid-onset generative genetic disorder that is dormant in the first year and a half of a child’s life, but ultimately claims the lives of young children before the age of four. Tay-Sachs disproportionately affected Ashkenazi Jews with 22 of 30 infants born with Tay-Sachs being Ashkenazi during the 1970s (2003: 45). A community based screening program was initiated in response during this time and had the support of doctors, rabbis, and Jewish community leaders alike. This led to the great success of Tay-Sachs screening, with over 310,000 Jews screened voluntarily by 1980 for the genetic disorder. Contrastingly, sickle cell anemia screening was a “public policy disaster” and “health and medical failure” (2003: 47). Although Tay-Sachs is much deadlier, sickle cell anemia screening became mandatory. There was distrust among African Americans towards the White medical providers that came to their communities to conduct genetic screening for sickle cell. Overwhelmingly, African American communities resisted these publically funded screening efforts. Ultimately, the Black Panthers became involved in community based screening efforts, but over-reported their findings of sickle cell anemia (due to the miss-categorization of carriers of the genetic disorder who would go on to live healthy lives) and the tension and hostility between mandated screeners, the screened, and communities only intensified. Regulatory laws for the screening of sickle cell anemia were therefore contentious and medical mistrust deepened.

Overall, the contrast between the social and political response to Tay-Sachs and sickle cell anemia highlight the importance of the types of communities a genetic disorder affects, the policy response, and the baseline relationships between healthcare providers and the communities affected.

Discussion: The Lasting Presence of Racial and Ethnic Categorization

In our discussion, a PMEPC fellow raised the issue of the significance of racialized categorization as described in Rosenberg et al.’s (2002) article and in philosopher Quayshawn Spencer’s article titled “A Racial Classification for Medical Genetics” (2018). The fellow emphasized how these two works provided evidence about the concordance between racial self-identification and genomic data organized by regional ancestry. This brought up the following questions: Are these socially defined population categorizations more than proxies of health behaviors and disease probability? Are racial categories substantiated in our genes?

Upon a closer read of Rosenberg et al.’s article, the authors delineate how “self-reported ancestry can facilitate assessments of epidemiological risks but does not obviate the need to use genetic information in genetic association studies” (emphasis added; p.2381). The data analyzed in that study was collected from the HGDP-CEPH Human Genome Diversity Cell Line Panel, which is “a resource of 1063 lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) from 1050 individuals in 52 world populations.” One of the major links observed by Rosenberg and colleagues was among populations who shared a language, however “linguistic similarity did not provide a general explanation for genetic groupings of populations that were relatively distant geographically” (p.2384). While Rosenberg et al. point to the use of self-reported population ancestry as a “suitable proxy” for genetic ancestry, they note that an exception to this are recently admixed groups “in which ancestry varies substantially among individuals” (p.2384).

Lastly, in his testing of philosophical premises for the use of racialized categories in genomic medicine, Spencer (2018) notes a scholarly work that claims that self-identified population samples had between 98.8% and 100% membership in the respective continental categories of “Asian,” “Black,” and “White” (p. 1020). Spencer goes on to describe how these numerical representations of self-identification with genomic population concordance do not accurately represent the relationship between these two concepts: the sample population for this particular study was of 3,224 “American” and “Taiwanese” adults and researchers deliberately excluded the “Asian” self reports from their South Asian subjects (Spencer 2018; 1020-1). Therefore, it is important to clarify in all scholarly works that although there may be links between self-identification and genomic variability, genomic data can be curated and presented in a manner that only tell one part of the larger story of disease risk probability for specific ethnic and racial populations.

As Dr. Sun highlighted during the discussion session, precision medicine is a misnomer. In fact, precision medicine could be best described as disease risk probability medicine where, based on available data genetic data (however categorized), healthcare professionals can provide disease risk probability information to individuals. As national data emerge regarding the variability of population genetics and health disease markers, perhaps a silver lining lies in that that the social determinants of health will be identified (as seen in Cooper (2005), Duster (2003), Krieger (2017) and Sun (2017)) and their effects upon populations attenuated.

Contributed by Sonia Mendoza-Grey

Cinnamon Bloss: "Consumers, Citizens, and Crowds in the Age of Precision Medicine"

Professor Cinnamon Bloss (UC San Diego) gave a fascinating talk for the Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics and Culture working group at the Center for the Study of Social Difference on February 15, 2018.

At the center of her talk was the problem of diffusion of medical innovation. This problem is not a new one. There is longstanding research on processes of adoption of innovation. Physicians as well as patients have historically hesitated to experiment with innovative technologies, and issues of privacy and trust have persisted. Inequality and distributive injustice has also traditionally been a problem as it is often wealthy individuals who enjoy innovative technologies long before they become standard therapies. A few historical examples are Serum treatment for pneumonia in the 1920s, Arsenic treatment for syphilis in the 1930s, Chemotherapy for varied cancer in the 1960s, and Experimental HIV treatment in the 1980s.

Professor Bloss engages with these complex and longstanding questions in her research in relation to Precision Medicine (PM). Her work addresses the considerable bioethical challenges that come with the rise of new technological innovation and practices of PM. And her analysis spans three analytical levels: individual, systemic, and societal.

What is remarkable and important about Professor Bloss’s work is that while many researchers take for granted that issues such as “privacy,” “trust,” and “participation” are challenges to PM, Professor Bloss adopts a critical perspective in trying to understand what those terms even mean in the arena of PM.

Instead of taking concepts from bioethics as given, she builds on previous work to empirically investigate the current bioethical dilemmas of PM. Her work is oriented to empirically understand the various norms, expectations and challenges entangled in the notion of “privacy” for patients. In what specific ways does ‘privacy’ affect trust and patient participation? And what are the current expectation of patients from PM?

Professor Bloss also attempts to understand the specific views of physicians towards PM and the specific gaps common to both clinical practice and PM. What motivates practitioners to turn to PM, and what obstacles prevent the diffusion of new technologies? On point of consideration is that transformation in the position of the FDA towards distribution of direct to consumer test results is especially important in shaping the current climate.

The significance of this research is in emphasizing that new technologies of PM transform the traditional concerns and problems for researchers, doctors, regulators and patients. We must continue to follow the evolution of notions and practices of ‘privacy’, ‘trust’, ‘regulation’ or ‘protection’ to understand current events.

In this context, Professor Bloss’s work on Direct to Consumer (DTC) strategies in PM is especially important, as it shows how the field of bioethics and its fundamental challenges are being transformed in a new healthcare economy.

In her research, Professor Bloss examines the American Gut Project to try and understand both new strategies for raising money for research (with the decrease in availability of public funding for research) and new models of patient consumerism. What drives Americans to participate in microbiome research? Which demographics are most likely to participate? What types of result do Americans expect? What if our ability to interpret the data and articulate its clinical implications is very limited? Are participants only interested in recognitions for their contribution to research or do they expect the data to help them manage their health proactively? And what will happen when we are able to interpret results and link microbiome profiles to clinical risks? Among other legal and ethical challenges, we might consider: would we have to report such results to employers and insurers?

Professor Bloss’s work opens up new avenues in understanding the new healthcare economy based on DTC and PM and their unique challenges. We are grateful that she so kindly and expertly discussed these topics with our PMEPC graduate fellows and the public at large.

Contributed by Moran Levy

Dr. Susan Markens talks about ethics and genetic counseling with the CSSD/PM&S Precision Medicine group

On January 22, 2018, the Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics, and Culture CSSD/PM&S working group welcomed Dr. Susan Markens (CUNY-Lehman College) for its first talk of the semester, titled The Genomic Revolution, Genetic Counselors, and “Doing Ethics.” Dr. Markens presented her qualitative findings based on her research about the perspectives of genetic counselors towards the increasing availability and use of genetic science and testing.

Dr. Markens focuses on studying how the new advances in genetic science are translated and perceived, particularly from the point of view of genetic counselors. She presented the following questions during her talk: 1) What are the perspectives of genetic counselors on ethical issues emerging from recent advances in genetic technology? and 2) What do they consider to be their goals and professional responsibilities?

The talk presented data primarily derived from forty-two qualitative interviews, the vast majority of which were with board certified genetic counselors. Additional supporting materials drew from attendance at professional conferences, webinars, and talks, and also newspapers and other publications.

Genetic Counseling as a Profession

Historian Alexandra Minna Stern defined the birth and development of the genetic counseling profession as a "quiet revolution,” in particular starting after the establishment of the first degree in genetic counseling at Sarah Lawrence College in 1969 and later of a certification exam in 1981. By the end of 2017, the United States had a total of 37 accredited programs and over 4,000 certified genetic counselors.

Previously, genetic counselors primarily worked in prenatal counseling and pediatrics, and their role is now expanding to topics related to cancer and multiple overlapping areas. Cancer counseling has grown alongside the scientific advances in the last decades, becoming more and more popular in an industry setting. Genetic counselors play a pivotal role in terms of translating information for patients, having both a background in the sciences and other psychosocial aspects. "Non-directedness" is considered to be among the tenets of the profession, but not without controversy, given professional's different existing approaches, fields of expertise, and perspectives. Nonetheless, patient autonomy always remains as the cardinal value.

In Dr. Markens’s interviews, many genetic counselors highlighted the uniqueness of their profession: one interviewee noted that "most other professions will recommend we just tell them what is available" alongside "benefits, limitations, and risks,” whereas genetic counselors describe themselves as providers of information, allowing patients to make decisions in an informed way. From a patient-centered perspective, their agenda consists in learning information about their patients, providing them information about genetic testing, and answering any questions that may arise.

Advances in and Impact of Genetic Testing and Knowledge: Views of Genetic Counselors

Overall, genetic counselors are enthusiastic about the advances in genetic science, calling it “positive,” “very exciting,” and “important.” In describing their motivation in pursuing their profession, one interviewee mentioned “empower patients to understand more about decisions” as one of their primary goals. At the same time, genetic counselors are aware of the complications introduced by such overwhelming “availability of information;” it is “frequently anxiety provoking,” leading to a “long line of testing,” “ambiguous results,” and “limited information.” As the stress behind “knowing the little things” accumulates, it “takes the fun out of pregnancy.”

Dr. Markens points to genetic counselors' nuanced understanding of pros and cons as “reflective ambivalence.” Where is the line between giving the “right amount” of information, and “just too much?” In being part of the process, genetic counselors see both sides of the coin, mentioning episodes in which they regretted providing additional information in talking with their patients. “Maybe we are testing too much given what we know right now,” commented one interviewee.

Dr. Markens reports genetic counselors pointing to the need to have solid justifications prior to ordering tests. There is a tendency to “just go ahead and test,” and some interviewees observed that it feels they are just ordering tests without thinking about it. As results come back with incidental findings, genetic counselors find themselves wishing they had not ordered as many tests. Often, results are unclear: “that level of uncertainty for people can be jarring. And for me as a clinician, I don’t like it either,” since it's “really hard to provide any level of reassurance to a patient.” All interviewees firmly confirmed that they are not “anti-testing,” but they expressed their efforts to grapple with the implications of their work.

The Role of Genetic Counselors in Private Industry

In highlighting the interaction between genetic counselors and the private industry for genetic tests, Dr. Markens introduced themes that highlighted 1) the role private industry plays in bringing genetic tests to market for consumers, 2) the impact that industry has had on consumers’ perceptions and choices for testing, 3) the interplay between academic channels of communication and clinical genetic counselors, 4) the implications of being a genetic counselor in the industry, and 5) how the growth in the private genetic testing industry impacts the expectations of both consumers and genetic counselors.

The impact of private industry upon the availability of testing for non-professionals has been of growing concern among genetic counselors. Specifically, there is a disparity between informed testing, with limited knowledge, and making informed choices for testing. The genetic counselors note that this ill-informed movement is driven by the industry's push for testing among all consumers (“there is a lot of push to get it [genetic tests] out there”). This has led to the transformation of genetic testing as a “part of the routine care” instead of an option under circumstances where the results would be informative for medical decisions.

Dr. Markens highlights how this push from the genetic testing industry has not been unidirectional, but rather has been in response to a growing demand from lay consumers. This interplay between the growing industry and consumer demand has been expressed in interactions between consumers and genetic counselors. The counselors, limited in number, have been inundated with demands for testing, often without consult; as one counselor notes “people want to do all this genetic testing without genetic counseling, and they maybe don’t really know how it could impact them emotionally and financially.” Due to the limited number of genetic counselors available, questions regarding how to inform all potential consumers and how to educate providers have come up in these interviews. The disparity between the need for clinical genetic counselors and the demand, as noted by the interviewees, is made more substantial by the rising demand for the counselors in industry.

In attending professional conference and webinars targeted for genetic counselors, Dr. Markens presented her observations about how the private industry interacts with counselors in these settings. Unlike other social science conferences, Dr. Markens noted that the resources allocated for the professional conference where genetic counselors would be present were primarily funded by private industry. Additionally, she observed that the drivers of research in the area of genetic testing was often from private industry groups and funded by pharmaceutical and testing companies instead of academic researchers.

Building from her observation at professional conferences and narratives collected through interviews, Dr. Markens highlights the implications of being a genetic counselor in private industry. Specifically, the increased demand from private industry has led to the creation of something akin to a pipeline between genetic counselors in training and industry jobs. Although not the initial goal of many counselors in training, “people are getting hired right away, and clinical positions are open because they are going into industry.” Dr. Markens notes that this has led to the creation of a significant paucity of clinical genetic counselors and the narratives from other genetic counselors has mirrored this, noting that the private industry counselors offer their services for counseling when there are not enough counselors available. This exchange brought up concerns about the conflict of interest between parties, where the industry counselor’s alliance may be to the company and not the consumer. In contrast to these perspectives by clinical genetic counselors, those counselors in industry see their role as being essential to be able to inform and change the industry practices from within.

In bridging the lessons learned across these narratives, Dr. Markens presented her findings on how to manage the expectations of all those involved in the genetic testing process. There was a resounding agreement across interviews that there is a need to ground the field in the research and actuality of what we know and do not know. Building from the perspectives on the growth of knowledge about genetics and genetic testing, there is a real need to “manage our expectations of what the testing is going to give us.” This has been most notably impacting the process of informed consent, specifically, seeking to clarify what it is that the consumer would want to know about the process and potential outcomes. Dr. Markens highlighted a “need to change our focus from the definition of ethical principles in their abstract form to looking at their practical application,” such that the realities of testing are no longer a hypothetical scenario, but rather a reality that is present every day in the lives of genetic counselors.

Follow Up Questions and Discussions

At the close of Dr. Markens’s presentation, the audience, representing a diverse group of practitioners, scientists, and members of the larger academic community, was left with many thoughts and questions. In this discussion were encompassed questions about the future of the field and how those still in training can be a part of the movement to revitalize the core precepts of genetic counseling. There was a call for more diversity in the gender and race of genetic counselors and a clarity in the training provided to instill confidence in counselors to inform not only the consumer, but also others within the medical profession.

Some way in which these changes are currently being implemented involve genetic counselors being the ones to sign-off on the types of tests that can be requested as well as providing training and intervention to physicians to better inform them of the choices they have for requesting tests. In reflection, the overall tone and temperament of those in the room was of hope and a willingness to be creators of change in this field.

Contributed by Natalia Romano Spica and Amar Mandavia

Kadija Ferryman: “Fairness in Precision Medicine”

Kadija Ferryman’s talk on November 30, 2017 for the Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics, and Culture CSSD working group drew from her post-doctoral project, “Fairness in Precision Medicine,” a study on which she is co-PI with danah boyd at the Data and Society Institute.

The question that motivates Ferryman’s work is: How do ethical and moral frames change the way we understand health data and outcome? Using content analyses of policy documents, observations of conferences, a mapping of major precision medicine projects, and interviews with 21 experts, Ferryman honed in on two sets of biases that various stakeholders recognized: embedded biases and biases in outcome. Regarding embedded biases, experts were concerned about biases in sampling of research data such as electronic health records. For biases in outcome, the stakeholders interviewed were worried about how precision medicine can exacerbate already existing inequalities.

Crucially, Ferryman emphasized that these biases should be thought about in relation to genomic data, but also the various data types that precision medicine relies on, such as electronic medical records, the “Internet of Medical Things,” and mobile and digital technologies. As such, Ferryman argued that those concerned about precision medicine should pay attention to discussions in “big data” and “algorithmic bias,” and that bioethics and “data ethics” could learn from each other.

In the meeting of the Precision Medicine working group the next day, several themes emerged from our discussion:

Correcting for Bias

A question raised during the meeting touched on how experts who recognize that bias exists can come up with strategies to correct these biases. For example, policy makers and researchers worried about diversity in precision medicine have made the recruitment of minority subjects a centerpiece of All of Us. This is also an instance of agreement on the existence of bias between different experts in precision medicine. Thus, finding more areas of agreement between different stakeholders is crucial in building the alliance of political capital, policy know-how, and technical expertise necessary to correct for biases that may arise with the introduction of precision medicine.

Different Data Types

From the standpoint of social scientists and humanists, the inclusion of different types of data in precision medicine efforts is definitely welcomed, as decades of public health research has recognized the importance of environmental and social factors in shaping health outcomes. Nonetheless, important questions here remain regarding the ability of precision medicine to reconcile the characteristics of different data types. For instance: How do biomedical researchers view these types of more qualitative data versus more quantifiable and “scientific” data types? How are different types of evidence evaluated by scientists? Relatedly, the work of linking disparate data types and recognizing patterns between them requires complex technical expertise. As such, more work should be devoted to thinking through how to integrate these various types of data to create a precise, but complete picture of an individual’s health.

Ethics in the Health Industry: “Precisely” Where Are We Headed?

Health and the data it generates are increasingly commodified. From private tech companies to healthcare providers, precision medicine ushers in greater opportunities to wield personalized health data for commercial use. This raises parallel concerns regarding the ethical use and handling of our personal information. From targeted Facebook shopping ads to Netflix recommendations, we trade our information and data privacy for access to services and convenience. Mass personalization at its current stage generally produces innocuous, if eerie, results. We retain a sense of autonomy and choice to partake in these services and disengage if we choose. As health and genomic personalization approaches arrive in the healthcare space, however, the ability to opt-out becomes much more constrained. Health is foundational in enabling meaningful engagement and participation in society. Greater integration of individual data into the healthcare system provides an opportunity for better care, but brings into question the genuine ability to opt-out of such a system in the future.

With the rise in personal health data spurred by the “Internet of Medical Things” (IoMT) and devices, we are afforded insight into not only genetic profiles, but behavioral, lifestyle, and environmental dimensions of individuals. Their implications extend beyond clinical contexts. Employers, not unreasonably, seek employee health data in pursuit of optimizing efficiency and a more productive workforce. More sinisterly, employment discrimination based on health is the next addition to contemporary concerns that include disability, race, gender, and sexual orientation.

Other ethical concerns flow more directly from technology and automated algorithms we increasingly use to analyze data. Our artificial intelligence and neural networks pick up the deeply ingrained racial and gender prejudices concealed within patterns of language, imagery, and social cues in our datasets. If we are not vigilant about policing these embedded beliefs, algorithmic bias may result in and reinforce discriminatory and exclusionary practices.

Involving the Community and Public Voice

Part of guarding against bias and discrimination involves engaging the communities directly impacted by this research. This may come in the form of Institutional Review Board (IRB) assessments or consulting local Community Board representatives drawn from the affected population. Even the selection of chosen representatives to give voice to a community, however, can be fraught with complications. How are such representatives selected -- by appointment or election, and by whom? Are those who end up on the Community Board truly representative of the community’s views? What are the power dynamics and hierarchies within that community influencing who is selected? In any structure, the intricacies of human relational and power dynamics play a tangible and meaningful presence, impacting the strength of community voice in discussion and decision-making. We need to be cognizant of such complexities when implementing structures and ensure they embody the representative democratic principles we value.

While the day-to-day responsibilities of IRB members largely involve checking off applications, on the macroscale, the arc and pattern of their decisions set precedents. As Ferryman poignantly questioned in discussing her role on the IRB board, “Are we the ethical conscience of a project?” A concern present in these circles is that passing IRB review or consulting Community Board representatives may become an ethics “check-off,” rather than a genuine partnership in understanding and appreciating the potential impact of their research on populations. We want and encourage research investigators, however, to consult ethics reviews and boards, recognizing they may not have the expertise to deal with these issues. “Seeking ethical assistance” is instinctive behavior we want to standardize in future precision medicine research.

As AI and health technology increasingly infiltrate daily life outside clinical contexts and the definition of health data is expanding, the modern role of bioethics may also need to evolve and cross traditional disciplines. Precision medicine is a collaborative effort that requires multiple perspectives. If this discussion imparted one actionable recommendation, it is that the scientific fields must call upon their ethical counterparts. Ethics is not an ancillary component of precision medicine, but a fundamental one in actualizing our communal vision for precision medicine.

Building Public Trust and Responsibility

The success of the All of Us study and other human genomic research requires the generous contribution of personal health and genomic data from individuals. This partnership between the public and science is needed to realize the network effects of a robust genetic database, and usher in a new model of precision healthcare that generations will benefit from. Building public trust is critical to these efforts, and without it, achieving a precision medicine approach will be a long and arduous process. While the U.S. culture naturally lends itself towards great suspicion of state power in these contexts, government imposes desirable safety regulations and constraints on profit-maximizing corporations. Designing ethical guidelines and a comprehensive regulatory landscape is important to enable proper oversight.

Conclusion: Ethics as a Partnership

Our unfolding discussion on the array of challenges that precision medicine poses increasingly points towards a more active and potent role of modern ethics in both industry and academic research. Precision medicine and our advancing abilities to arrange massive amounts of data herald great promises for our capacity to improve human health, behavior, and lifestyles. We must ensure ethical and regulatory safeguards keep pace with these abilities and align them with our core values on equity, fairness, privacy, autonomy, etc. Protecting these rights and evolving policy to reflect these ethical principles is key to ensuring our society does not stray onto a dystopic path.

Contributed by Larry Au and Jade H. Tan

“The Economics of Precision Medicine and Disparities in Health,” a talk by Dr. Kristopher Hult

The second Fall 2017 talk of the CSSD working group Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics, and Culture (PMEPC) featured Dr. Kristopher Hult. In his presentation, “The Economics of Precision Medicine and Disparities in Health,” Dr. Hult shared his research and outlook on the potential of personalized medicine to increase the health impact of existing treatments, and thereby improve patient outcomes.

Balancing Treatment Efficacy and Risk

Dr. Hult used multiple sclerosis (MS), a progressive autoimmune neurological disorder, to highlight how personalized medicine may be able to improve clinical care. Existing therapies for MS differ considerably regarding their efficacy and risk of side effects between patients, making accurate assessment of patients’ individual responses highly valuable. For example, Tysabri, a leading immunosuppressive drug, can lead to progressive multifocal encephalopathy (PML), a debilitating neurodegenerative illness; however, the risk varies over 10-fold across patients. Through using genetic information and other molecular biomarkers, such effective medications can be targeted to patients who have the lowest risk, helping balance treatment efficacy and risk.

Innovations and the Market

Dr. Hult also presented a case for the potential of incremental innovations on existing FDA approved molecules or therapy. He discussed a quantitative model to assess the effects of policy interventions on innovations and how existing policy to incentivize orphan diseases can differentially affect incremental innovation with respect to novel innovation. While such policies have spearheaded the creation of new therapies, they can also lead to corporate exclusivity, increasing the market price and reducing subsequent innovation. In addition, the promise of exclusivity may further encourage corporate entities to utilize precision medicine approaches to find novel biomarkers, so that they can show that their agent is effective for a narrower segment of the population and thereby market it as an “orphan drug.” The long-term implications of such approaches on pharmaceutical innovation and patient care are unclear at present. Ultimately, evaluating the effects of novel vs. incremental innovation requires comprehensive understanding of the factors that determine health outcomes, such as the impact of a drug on the length and quality of life, cost of the drug, and accessibility of the drug and insurance. However, as Dr. Hult acknowledged, the medical actionability of a disease is ever-shifting, making it difficult to accurately estimate these values.

Precision Prevention

The potential of personalized and precision medicine extends beyond the population who are already sick. It also has the promise to identify healthy individuals at risk, and prevent disease through targeted therapy, with “precision prevention” practiced on a broader scale. However, doing so involves significant financial considerations, and as healthcare spending continues to rise, there is a need to accurately measure the cost efficacy of the interventions proposed. As health systems across the globe shift to policies that prioritize value as well as volume, such considerations are of prime importance. As Dr. Hult noted, personalized medicine promises to revolutionize the production and targeting of pharmacotherapy, and his talk provided a valuable economic perspective on how to evaluate its impact on healthcare innovation and outcomes.

Contributed by Neha Dagaonkar and Emily Groopman

A Human Origin Story in the Age of Biotech, Race, and Science: A Talk with Priscilla Wald

Priscilla Wald, Professor of English and Women’s Studies at Duke University, presented her talk “Cells, Genes and Stories: HeLa and the Patenting of Life” as part of the CSSD project Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics and Culture, followed by a discussion with the Precision Medicine working group in September.

A Particular Narrative of Human Origins

The discussion challenged the working group to consider the following: What does it mean to be human in the age of biotechnology? What defines being human? Is there a delineation, by which we are human on one side and non-human on the other?

Dr. Wald pushes these fundamentally humanistic questions to the forefront, and asks us to question why they matter. Why is our human-ness important to distinguish? In a thought-provoking account of the ethically-charged events surrounding the history of genetic engineering, she suggests a compelling human need to create a narrative about our origins – a narrative about the origin of humanity.

Among anthropologic creation myths and religious creation stories, scientific evolution is itself a particular narrative and attempt to understand ourselves and our place in this world. Modern genetics enables us to reach our arm further into our origin and kinship stories than before. To be part of some broader meaning is a potent need, and the methods we use to understand who we are as a species need careful consideration.

Social Fears and Biotechnology

These human questions are echoed in our concerns about new genetic technologies – we carry our social fears and taboos like a sack, passing it from new biotechnology to biotechnology. The exact set of questions which probe technology’s implications for our “humanity,” “being human,” and “sacred life” follow us. What is once unthinkably horrific at its advent – organ transplantation, IVF reproduction, and now genetic tinkering and artificial wombs – becomes medicalized and mundane with implementation. Without particularly negative technological repercussions, we forget and move the sack of concerns forward onto the next potential biotech invention.

Questions of patenting and intellectual ownership of living molecules have risen to prominence in the legal sphere during the last few decades, alongside the rise of biotechnology’s presence in science and our lives. Diamond v Chakrabarty (the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that the living nature of a genetically-modified organism is no bar to patentable subject matter) and Moore v Regents (a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that denied a property ownership right to one’s cells) both herald the shape of legal questions to come in this new age of biotech commercialization.

Race, Genetics, and Racism

If there is one pressing certainty that arose from the discourse, it is that we cannot venture further into this future of new genetic capabilities without understanding the deeply social implications of its effects. Race is a social category, not a biological one – yet genetics plays centrally into many racist narratives. Racism as much as race affects health outcomes. Humans are 99.9% identical, but it is the 0.1% that is most often explored, plumbed for its depths, and commercialized. 23&Me and similar genetic analysis organizations capitalize on this interest, rising to meet demand for an ethnographic narrative of our origins, but falling far short of providing real accuracy or insight for what individuals seek to discover about themselves.

The truth that may be most difficult to remember in the coming years of the Genetic Age is that we are not a sole product of our genetics. We are an amalgamation of our genetics, environment, society, and the complex interactions and reactions of those dimensions in epigenetics. Dr. Wald convincingly pushes us to return to questions about which particular narrative is being advanced about human origins, ‘us versus them’ kinship groups, and the motivations that underlie the narrative and why.

Science, Media, and the Markets

Social and institutional power structures determine who decides what is done with the data, and what stories are told about the data. Modern genetics is a form of biopolitics and power. When technology is controlled by capitalism, and when it is for commercial use or entertainment, who will pay for the technology becomes a defining question.

Above all, this discussion surfaced a highly persuasive case for cross-collaborations of the humanities and science, most especially in the communication of genetics research to the public – a conclusion that affirms this working group’s essential purpose and need. Linguistics, English, Philosophy, and their sister-humanities disciplines provide the insight and expertise on the medium by which all information is mediated and communicated: language. It is a medium that can be both uplifting and beautified, or subverted and yoked for alternate purposes. In communicating science to the media and public, we share the burden of responsibility for ensuring an accurate education.

Contributed by Jade Tan

Jackie Leach Scully Discusses Precision Medicine, Embodiment, Self & Disability

On March 9, 2017, Dr. Jackie Leach Scully, Professor and Executive Director of PEALS (Policy, Ethics and Life Sciences) Research Center at Newcastle University in Newcastle, UK, led a thought-provoking and insightful seminar and discussion on "Precision Medicine, Embodiment, Self & Disability" as part of CSSD's project on Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics and Culture.

Dr. Scully largely explored biomedical perceptions surrounding disability, and proposed how these perceptions are and will continue to change within the era of precision medicine. Traditionally, biomedical views have largely considered disability as a nominative and quantifiable pathology with less consideration for cultural, environmental, social, economic and political aspects. And while precision medicine remains rooted in this conventional biomedical perspective, rapid advances in the field are posing new bioethical questions and challenges that will continue to shape not only the biomedical but also the social/societal perceptions of disability.

Dr. Scully dove into a variety of such issues that we are currently facing and those that will likely be forthcoming. For example, paradoxically, individualized probabilistic data of genomic abnormalities obtained in the preconception/prenatal setting can effectively uncouple genetics from physical manifestations (the “walking ill”), thereby resulting in unjust discrimination—where the concept of disability exists prior to the individual’s embodiment and identity have taken form. This challenge reflects the central question of how precision medicine’s attitude toward “disability” differs from that of “disease.” While medicine in general rationalizes the avoidance or elimination of disease, will this rationalization inevitably apply to genetic variation associated with disability? And how will our society come to these decisions regarding what type of genomic variation we consider “abnormal” and appropriate for preconception and prenatal modification such as through preimplantation genetic diagnosis or in the near future, gene editing techniques.

With the surge of funding for precision medicine research over the past three years, Dr. Scully makes the case that we should allocate a portion of this funding to monitor the ethical ramifications surrounding these biotechnological advances in effort to keep up with the rapidly evolving landscape of precision medicine.

Contributed by Liz Bowen

Jacqueline Chin Presents on "Precision Medicine: Privacy & Family Relations"

Dr. Jacqueline Chin, Associate Professor at the Centre for Biomedical Ethics, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Singapore spoke in February on the subject of "Precision Medicine: Privacy & Family Relations" for CSSD's project on Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics, and Culture. Dr. Chin's presentation underscored the leading pillars of privacy and family relations in connection with precision medicine. She espoused several focal points through which a humanistic conceptualization of the relevant issues might be achieved, including: the metaphor of precision medicine itself, the problem of genetic privacy, pragmatism and frameworks of choice, and enabling responsible choices in the context of precision genomics.

The Metaphor of Precision Medicine

"Precision Medicine" (PM) implies a certain model of medical care that is personalized and tailored to the individual. But “precision” itself is a cultural construction. The term connotes accuracy, and favors results that should be shared, generalized, and standardized, as opposed to ones that can be true about an individual case. In acknowledging this tension, Dr. Chin argued that PM amounts not to individually tailored healthcare, but rather to genetically based healthcare. Is precision necessarily a social or physiological “good”?

By all accounts, central to PM is conceptualizing “genetic information.” As the literature makes evident, there is little consensus about what genetic information even is. Indeed, countless debates concerning when and on what basis genetic information is significant and to whom—and when such information should be kept private—continue to proliferate. The group found that these realities bring to light an important tension that should be qualified in our humanistic conceptualization of such emerging medical approaches, which is distilling whether PM is specific to an individual versus to a cohort of individuals that share a particular common trait or disease. On a more granular level within this framework, one might distinguish between the clinical versus research uses of the genome. That is, in the clinical context, the purpose is to deliver diagnostic and treatment information to a treating healthcare provider, and in the research context, a researcher is conducting a genetic analysis to explore a specific hypothesis that is independent of diagnosis or treatment for any one individual. We acknowledged that in these settings, from a privacy/disclosure perspective, the individual human subjects are not necessarily informed of the results of genetic analyses, and it was argued that healthcare professionals and ethicists ought to calibrate such communication practices with deference to ethical guidelines and patients’ rights. Thus, when we conceive of the PM metaphor, such distinctions and considerations are of import.

Precision Medicine & Genetic Privacy

Dr. Chin articulated that the term “genetic privacy” can be problematic when taken at face value (e.g., as if there were something exceptional about genetic information that necessitates special ethical attention or legal protections). Instead, she suggested starting with the observation that a general problem of privacy occurs when technological feats (such as data capture and storage, processing, and retrieval) are accomplished. In reflecting upon this conundrum, an important inquiry surfaced: Given the proliferation of public and private sector genetic databases and genomic research, and in light of function creep (e.g., the benefits of using technology in new ways), how might we reconcile attempts to somehow “draw the line” in crafting regulations/policies that protect identifiable information yet also leave room for advances in genomics? In grappling with this challenge, identifying the stakeholders is key.

Pragmatism and Frameworks of Choice

Chin discussed with the group precision medicine in connection with social and familial obligations. The dialogue centered on (i) reflections of pragmatism and (ii) what medical anthropologist Margaret Sleeboom-Faulkner terms “frameworks of choice.”

Drawing on philosopher Herman Saatkamp’s work, discussants considered the argument that pragmatism prioritizes the good over truth, and the idea that pragmatism is a vehicle for assessing what he terms the “new genetics.” What is perhaps most important here is embracing the complexity of the connection between genes, environment, and culture, and accordingly the urgency to redirect research efforts to developing “responsible” individuals. But many issues remain with regard to this line of thought, and a plethora of questions were raised in our seminar. For example, how might we define a responsible parent, and to what extent is that definition fluid? To what degree is being responsible context-specific, and is it a product of free will exclusively, or a combination of other forces within us, our environment, and our culture? Finally, how possible is it to achieve a pragmatic directive for parents to use genetic information in child rearing? While these issues cannot be solved in a brief discussion, one of the prevailing arguments asserted that given the complex biological and societal nature of human beings, single genetic traits are likely less responsible for determining complex human actions, whereas the perspective that draws upon both genes and environment is more convincing.

The other work we reviewed in this context is that of Sleeboom-Faulkner’s frameworks of choice writings. What was most thematic in our discussion was that while reproductive governance is a function of social individuals and of the state’s regulatory impositions, the reality remains that individual choice and free will wildly varies depending on the context (for instance, in response to community and cultural norms, which may produce coercive or poorer outcomes). Additionally in this vein, one’s choice has the potential to be constrained or restricted by social and economic limitations, such as conflicting religious values or financial barriers that prevent or disable access to a given genetic test or treatment. As Sleeboom-Faulkner argues, the relative bioethical permissiveness of state and local governments influences the degree to which populations participate in, and benefit from, genetic testing.

Precision Genomics and Enabling Responsible Choices

Another issue that Dr. Chin emphasized related to precision genomics and enabling responsible choices. The topics she highlighted included the importance of the force of the law in protecting individuals from being coerced into undergoing genetic or whole genome testing, and the notion of sharing such test results “responsibly.” In considering the latter, for instance, what might be an appropriate way to arrive at decisions to inform next-of-kin in consideration of family members’ interests? In a perhaps-controversial conviction, Dr. Chin posited that individuals who undergo genetic or whole genome testing should be required to consent to sharing relevant results with close family members who desire to access the information. She argued that families should be notified so that they can choose whether or not to apply for access to a family member’s findings and undergo testing themselves. This set of claims produced a wave of skepticism among some working group members, who questioned what the scope of the “family” would entail (e.g., “close” family? Only those with whom one can establish trust? All blood relatives? Would it also include people with whom they are thought to have a reasonable degree of trust in?), and to what extent moral, relational, or other civic duties might bolster or compromise such an obligation to disclose. Another response underscored the notion of risk stratification: as it stands now, PM is more so an issue of risk, as opposed to identifying a particular variant that may be indicative of someone’s potential to inherit or develop a particular condition. So perhaps the extent of the obligation to disclose hinges on the notion of actionability—the degree of information that is actually useful to patients or not. To calibrate, Dr. Chin did acknowledge that the right of individuals not to know and to make their own judgments about the risks to privacy of undergoing genetic testing should be protected. Still, a strong argument in favor of disclosure remains, which is that PM succeeds only if people do share information—in essence, sharing information is part of the “deal” of PM, and without it, PM may not materialize as expected.

Contributed by Matt Dias

Jackie Leach Scully Speaks on Precision Medicine, Ethics, Politics, and Culture on March 9

On March 9th, the CSSD project Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics and Culture will host Jackie Leach Scully for a lecture at Columbia. Leach Scully is Professor of Social Ethics and Bioethics, and Executive Director, Policy, Ethics and Life Sciences Research Centre, Newcastle University, UK.

Professor Leach Scully asks how the enormous recent advances in genomic knowledge and capabilities might affect the public's understanding of embodiment that is disabled. How might precision medicine influence thinking about and attitudes towards disability, and disabled people, in the future?

Read more about the event here.

Jacqueline L. Chin Discusses "Precision Medicine, Privacy, and Family Relations" on February 9

On February 9, the CSSD working group Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics, and Culture will host a discussion by Jacqueline L. Chin, Associate Professor, Centre for Biomedical Ethics, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, on the topic of "Precision Medicine, Privacy, and Family Relations."

Chin posits that a better understanding of genetic information not only enables the linking of genetic identity to conceptions of disease, treatment and prevention, but offers the possibility of using information mining techniques (such as comparison with bodies of data about environment and lifestyle, and stratification of information) for refining disease classifications, refining risk assessment by determining individual risk, and targeting treatment and preventive behavior. Much of the attraction of precision medicine, in Chin's view, is driven by glimpses into the complex base of human life, the desire to understand current health statuses and future health implications, and the concentration of power in big data. This evolving metaphor is bound up with other important ones, including powerful stories of people wishing to have or not have knowledge about future health, depending on how such choices and their ramifications are framed in their context. Exploring the ethical debate on ‘genetic privacy’, this lecture offered some examples of how social debates about the goals of genomics are helping to structure individual and family decisions. Chin asks how precision medicine initiatives in different parts of the world can foster citizen participation in defining the goals of genomic medicine.

Ruha Benjamin on “Can the Subaltern Genome Code? Reimagining Innovation and Equity in the Era of Precision Medicine”

In November, Ruha Benjamin, Assistant Professor in the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University, visited CSSD’s Project on Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics, and Culture to argue for a re-imagining of innovation and equity in the era of precision medicine. Her presentation, “Can the Subaltern Genome Code?” presented a number of competing struggles over the future of precision medicine, positioning the field in a contemporary landscape of racialized inequality and disparities in access to genetic information.

The stakes of precision medicine, Benjamin explained, involve thinking through the underlying reasons for scientific intervention in human genetics. She emphasized that it is crucial for stakeholders involved in the creation and imagination of precision medicine’s possibilities to also reimagine inequality as a concept with biological underpinnings.

Benjamin critiqued the life sciences’ claims to be able to arbitrate the reality of race—particularly genomic researchers' attempts to establish a biological basis for racial difference—and emphasized that questions remain about the racialized aspects of who has the power to translate and interpret genetic information. (Hence the question: Can the subaltern genome code?)

Benjamin also challenged the policies of some states, like the U.K. and Kuwait, that have adopted border-control and information-gathering policies based on the notion that social differences such as ethnicity and nationality can be verified with genetic groupings. This false diagnosis of identity brands national populations as biologically distinct, and thus naturalizes boundaries, instead of celebrating genetic sovereignty, Benjamin said.

Benjamin highlighted the importance of imagination as a tool to think through ethical challenges that arise with advances in genomic science. She cautioned the thinkers and creators of precision medicine to be vigilant about the potential for the creation of hierarchies based on genetic differences. Those who invest in biotechnology don’t limit themselves to the “realistic” when it comes to imagining the possibilities of precision medicine, she reminded the group, inviting those who are concerned about genomic science’s ethical stakes not to limit their imaginations for alternative possibilities, either.

In a working group session the followed, members continued to examine the question of inequities by applying questions of bio-constitutionalism to the realities of the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI).

Responding to group members’ questions about informed consent and informed refusal, Benjamin introduced the idea of a consent framework known as “DNA on loan”—a means of navigating genomic rights among marginalized groups. Within this framework, Canadian researchers collecting genetic information from First Nations tribes cannot simply obtain one-time consent, but must return to the community and ask them to re-consent as research progresses.

Building on these concepts, the question of the “right not to know” was brought forward as an issue of informed consent. With increased knowledge of genetic predictors of illness coming forth as a result of initiatives such as PMI, group members argued, questions of consent apply not only to participation in studies, but also to the potential for knowledge of a genetic risk for an illness. With a growing effort to identify relationships between genes and manifestation of illness, what are the limits to informing the participant of potential statistically, but not clinically, significant genetic findings?

Benjamin pointed out that consent starts with incorporating the reality of the participant as a part of the process—that it is not simply a single moment of consent, but a process of building a relationship. By shifting the onus of responsibility to provide pertinent information from the participant to the clinician/researcher, Benjamin suggested, researchers can begin to enable the subaltern to genome code.

To achieve such an empowering person-to-person connection requires a restructuring of the foundation upon which clinicians are trained: not in cultural competency, but rather in cultural humility. Benjamin advocated for physicians to broaden their perspectives beyond what they need from the participant, and instead attend to what narratives and experiences the participant brings to the clinical encounter.

Contributed by Amar Mandavia & Fatemeh Adlparvar

Aditya Bharadwaj Discusses Cultivated Cures: Ethnographic Encounters with Contentious Stem Cell Regenerations in India

In October, the CSSD working group Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics and Culture hosted Aditya Bharadwaj, Professor of Anthropology and Sociology of Development at the Graduate Institute, Geneva, who presented his work on “Cultivated Cures: Ethnographic Encounters with Contentious Stem Cell Regenerations in India.”

Bharadwaj’s research generated a provocative discussion on the diaspora of stem-cell research and its ecological detriments in India, leading the discussants to explore caveats of cure, disease and illness from the perspective of communities that reside in the fringes of Indian society.

Bharadwaj questioned his own position as a scholar-researcher who investigates and gives voice to the rural and largely invisible people of India. He also questioned the dogmas of Western models of scientific research and the ethical dilemmas that govern their approaches to the study of human suffering as experienced by marginalized groups.

Bharadwaj opened his talk by posing alternative conceptualizations of illness and health. Health, generally considered to be a normative or neutral state, was redefined as a dormant state without evident disease or illness. Health and disease co-exist within the body and a paradigm shift is required to understand the state of good health as not a mere absence of disease, but rather a dormancy of disease, according to Bharadwaj. In a nutshell, “health exists in the moments when disease sleeps and is cast aside when disease awakens.”

Bharadwaj emphasized that the prevalence of problems like underdevelopment, malnutrition, and disease in many developing countries, including India, are a direct result of pressures created by a corporatist intelligentsia and market-driven socio-ecological changes that degrade living environments. The global hegemony of Queen Victoria’s Britain was central to this process, neglecting the social justice concerns and ecological sanity of indigenous people, he claimed.

The group discussed the need to redefine and decontextualize “justice” while researching the indigenous diaspora. The guidelines of scientific and behavioral research into fringe cultures, including clinical trials, are defined by teaching professionals from elite institutions in developed countries, leading to incorrectly assumed prophylaxes and etiologies of illness, the group agreed.

The group discussed the possibility of creating a middle ground within an eco-politics strategy that might be more inclusive of indigenous cultures and benefit affected communities more directly. Due to India’s lack of evidence-based baseline and needs-assessment indicators, investment projections for stem cell research remain ambiguous.

The group also discussed how health care and social markets function differently from business markets. Bharadwaj explained that efforts to develop and incorporate indigenous methods of “cultivated cures” and treatment should be prioritized and valued, in order to balance the impact of more modern models of care that are standardized in the developed world.

In response, many in the group questioned the science behind this model. Coming from the tradition of Western science, some defended the need for peer-reviewed articles and government oversight. Without this structure, some cautioned, clinics in developing communities may be able to dabble in pseudoscience and peddle “cures” to desperate patients without power or choice.

Contributed by Srishti Sardana & Christopher Cadham

James Tabery Traces History of The Human Genome Project with CSSD's Precision Medicine Working Group

On September 15, the Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics, and Culture working group kicked off its first semester with a talk by James Tabery, Professor of Philosophy and Medicine at the University of Utah.

Tabery’s talk on “Collins’ Cohort: The Path from The Human Genome Project to the Precision Medicine Initiative” provided historical perspective on the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI) announced by President Obama in his 2015 State of the Union address, a plan to recruit a cohort of 1,000,000 or more American volunteers to provide biological, environmental, and health information over an extended period of time.

At the time, Tabery explained, the proposal made headlines because of its ambitious scope and exciting medical promise. The idea, however, was not a new one. As the Human Genome Project was wrapping up in 2003, the director of the National Human Genome Research Institute sought to set the NIH off on another bold genetic initiative—to create a large, longitudinal, national cohort that would allow for examining the genetic and environmental contributions to health and disease. The path from that initial idea in 2003 to the public announcement at the State of the Union address in 2015 was marked by technological advances, logistical challenges, ethical dilemmas, and political hurdles. That historical legacy also reveals a great deal about what we can expect (and not expect) from the Precision Medicine Initiative.

Tabery reviewed the history of successes and failures among previous initiatives such as the American Family Study, The American Genes-Environment Study, and the Genes, Environment, and Health Initiative. With the 2015 State of the Union address, he explained, the dream of Frances Collin, director of the NIH, was realized. The PMI would seek to enroll 1 million people in a cohort reflecting the diversity of the US population, with the goal of creating personalized clinical care based on genes, environment, and lifestyle. It would aim to provide personalized, clinical care for both rare and common disorders, as well as learning about what makes people healthy.

Some of the worries about PMI are unfounded, according to Tabery. Although many worry that the PMI is moving too fast, history tells us that it is the product of over a decade of thought. And although some also worry that the PMI will fail in its goal to recruit a million subjects, Tabery claims that Collins will deliver.

A more serious concern regards what it would mean for the PMI to succeed. Since the PMI is really concerned with genetic, there is a lot of talk about the environmental factors that cause disease but little attention to specifics. Since other countries are already doing these kinds of studies, some ask why the United States should replicate their work? And finally, Tabery wondered whether the sample collected will really be representative.

Tabery closed by reminding his audience that the PMI is a work-in-progress. Given that Columbia is one of the enrollment centers, this is an exciting time to be thinking about the questions raised and to witness, on the ground, how they are addressed.

Photo above is of members of the Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics, and Culture working group.

Rachel Adams Publishes Article about Japanese Massacre and Ambivalence Toward People With Disabilities

Rachel Adams, CSSD Director, Professor of English and American Studies at Columbia University, and director of the CSSD project on Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics and Culture, recently published an article in the Independent on the universal ambivalence toward people with disabilities.

Citing the largely unacknowledged July stabbing deaths of 19 people in a home for the disabled outside of Tokyo, Adams writes that "The practice of warehousing people with disabilities sends a message that they are less than human."

According to Adams, while people with disabilities gain more rights and are increasingly more visible, they continue to face prejudice, social isolation, and violence. Stigmatization leads to institutionalization, but "In truth, disability is an aspect of ordinary experience that touches all people and all families at some point in the cycle of life," writes Adams.

Read the full article here.

Precision Medicine Working Group Presents Aditya Bharadwaj, October 13, on "Cultivated Cures: Ethnographic Encounters with Contentious Stem Cell Regenerations in India"

CSSD's Precision Medicine working group presents Aditya Bharadwaj, Research Professor, The Graduate Institute, Geneva, on "Cultivated Cures: Ethics, Politics, and Culture Ethnographic Encounters with Contentious Stem Cell Regenerations in India" on October 13th, 2016 from 5-7 p.m. at 754 Schermerhorn Extension.

The lecture seeks to conceptualize how we might understand a scene of chronic and progressively pathological affliction as a site for witnessing the anatomy of a cultured and cultivated cure from within the emergent field of regenerative medicine. The argument seeks to probe how this allows us to see a progressive and aggressive affliction as paradoxically regenerating in the face of curative operations that end up maintaining a tenuous truce, a dormant zone that can be imagined as health. This fleeting ‘health’ wedged precariously between a cultivated cure and a regenerating affliction offers fascinating insights into the emerging world of stem cell therapeutics.

The event is free and open to the public. Columbia University is committed to creating an environment that includes and welcomes people with disabilities. If you need accommodations because of a disability, please email Liz Bowen, at elb2157@columbia.edu, at least two weeks in advance.

Rachel Adams Directs New CSSD Group Addressing the Ethical, Cultural, Political, and Historical Questions Around Precision Medicine

CSSD is initiating a broad-based exploration of questions raised by precision medicine—an emerging approach for disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle for each person—in such fields as law, ethics, social sciences, and the humanities.

Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics and Culture will be the first project of its kind to bring faculty from the humanities, social sciences, law, and medicine into dialogue with leading scholars from the United States and abroad to discuss how humanistic questions might enhance the understanding of the ethical, social, legal, and political implications of precision medicine research. A series of workshops and lectures will explore the mutual benefits to humanists, social scientists, researchers, and clinicians of serious interdisciplinary engagement with this emerging medical field.

The next event, on Thursday, October 13, 2016, from 5-8 p.m. at 754 Schermerhorn Extension, is a discussion with Dr. Aditya Bharadawaj, Professor of Anthropology and the Sociology of Development at the Graduate Institute, Geneva, on "Local and Global Dimensions of Precision Medicine."

Rachel Adams, CSSD Director and Professor of English and Comparative Literature, Columbia University will direct the project with support from Columbia’s Humanities Initiative.

Topics the project plans to address include how the use of genetic information changes understandings of self, agency, health, embodiment and ability; how precision medicine might intersect with the movement for patients’ and disability rights; historical perspectives that may illuminate the development of precision medicine in the present; how cross-cultural understandings of medicine, health, and ability might contribute to Euro-American approaches to precision medicine; how precision medicine might change the ways care is given and received; how precision medicine is understood by popular media; and the benefits and drawbacks of a “big data” approach to research and treatment.

CSSD’s project is part of Columbia’s larger overall Precision Medicine Initiative, which aims to establish the university as the center for scholarship relating to precision medicine and society. In 2014 Columbia University President Lee C. Bollinger announced a University-wide initiative to address the vast potential for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease based on the genomic and other data that precision medicine provides.