Wendy Vogt, Professor of Anthropology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, discussed “Rape Trees, State Security and the Politics of Sexual Violence along Migrant Routes in Mexico.”

Vogt said that along the U.S./Mexico border, Central American immigrants have become simplistically associated with sexual violence and thus used as scapegoats for the consolidation of U.S. political power. Vogt claimed that actually half of all sexual assaults happening at the border are perpetrated by migration employees and not migrants.

Vogt said that a series of assumptions and biases against migrants are employed to justify draconian governmental policies. At the local level, migrant men are customarily viewed as sexual predators and criminals while migrant women are considered suspect as sex workers. Migrant shelters then become marked as alleged rape sites, receiving complaints and threats from local populations, all of which then legitimizes militarized police tactics against migrants. Similarly, conservative news outlets on the national level have reported on “rape trees” along the border that are hung with the undergarments of the alleged victims of rapes perpetrated by Mexican criminals and “coyotes.” These unsubstantiated stories proliferate and are used to confirm the suppositions of sexual violence perpetrated by encroaching migrants.

“Such discourses allow the re-inscription of the US nation as chaste, while erasing the complicity of the US government in long term policies that have caused migration,” said Vogt.

Diana Taylor, University Professor of Performance Studies and Spanish and Founding Director, Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics, NYU, discussed the Madres of Central American Migrants movement.

Starting in the 1970s, these traveling “caravans” of mothers and families of the thousands of Central American migrants who have disappeared as they travel through Mexico on their way to the United States aim to connect families of the missing migrants and raise awareness about their fates. The Madres also speak to the United States’ increased attempts at controlling the tide of migrants coming from Mexico.

Stopping at local jails, brothels, and detention centers, caravans embark on fact-finding missions and have become a crucial part of the human rights strategy in Central and South America, said Taylor.

One key way in which the Madres functions is to create a meme—an image, a movement, a story—that transmits the grief and trauma involved in a direct fashion that is both simple and replicable. Successful memes like the Madres materialize everywhere U.S. state policy is used to “disappear” unwanted individuals. The militarized border, changing labor laws, and the war on terror were all cited as examples.

Taylor said the Madre movements have produced signs of hope, as in Argentina, where many of the people responsible for political killings there have been exposed and imprisoned.

Chloe Howe Haralambous, graduate student in English & Comparative Literature, Columbia University, spoke about “Suppliants and Deviants: Gendering the Refugee/Migrant Debate on the EU Border.”

Haralambous said that recognition of refugee status is the only guarantee of entry into Europe and that those individuals labeled economic migrants are not given that privilege. For example, in the current refugee crisis, unwanted Iraqi and Afghan immigrants have been treated as economic migrants in an attempt to artificially reduce the number of people Europe must protect, she said.

While women are considered “less dangerous” and are usually guaranteed entry over young men, “There is no distinction between helpless refugees and unworthy migrants,” Haralambous protested.

This sorting by gender leads to unfortunate results, such as half of the victims of sexual assault in refugee camps turning out to be young men and women sometimes disowning their husbands so they can improve their odds of gaining entrance. Thus, the refugee is characterized as grateful and helpless while the economic migrant is imagined as sneaky and undeserving, said Haralambous.

“In the mainstream, you are either a compliant and suffering refugee or a rapacious economic refugee,” she said.

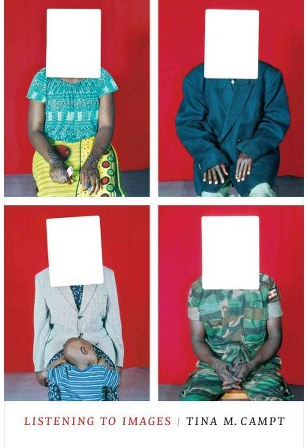

Isin Önol, Curator in Vienna and Istanbul, spoke about her exhibit, “When Home Won’t Let You Stay: A Collective Deliberation on Taking Refuge.”

The show attempts to elucidate the journeys of the displaced between their lost homes and the new ones they will have to build, said Onol, but it also seeks to bring people of disparate experiences together.

“It interrogates what it means to be human today, in contrast to the ideals of humaneness and human rights,” Onol said of the exhibit.

While human beings can excel at organizing for evil, they can also organize for good, she said, referring to the structural violence that newcomers can experience and the experience of those who might remain passive in the face of that violence.

In the Q&A period that followed, the panelists were asked what journalists could do to ameliorate the situation. Haralambous said journalists would do well to address the structural causes behind the refugee crisis, since media contributes to the normalization of these events.

Vogt underlined the fact that traditional gender narratives were also being used to distort the narrative and that this actually enabled compassion fatigue. Instead, “We should point to people’s resilience—we should encourage alliance, not empathy. We should be motivated by the possibility of solidarity,” she said.

Photos from the discussion are posted here and a video of the discussion can be viewed here.

Contributed by Terry Roethlein and Liza McIntosh